'THE GREAT WAR', 'THE WAR TO END WAR', 'WORLD WAR 1'

'What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

- Only the monstrous anger of the guns.'

from 'Anthem for Doomed Youth'

by Wilfred Owen

31st MAY - 1st JUNE 1916

THE NAVAL SEA BATTLE

OF JUTLAND

Transcript from: 'More Sea Fights of the Great War'

by W.L. Wyllie, C. Owen & W.D. Kirkpatrick

pub. 1919

CHAPTER VII At one moment the gallant ship was rushing through the Waves crowded with hundreds of the best fighting men our breed produces, all in splendid health, full of life and energy. In the -next only torn fragments of steel and men remained. The foaming waters rushed in and covered everything, the great grey cloud drifted north and gradually dispersed into filmy vapour. All was over, and Indefatigable had gone for ever. Admiral Evan Thomas's big battleships now began to take their part in the action with 15-inch guns firing when able on the German light cruisers. The range of the enemy from their line was from 19,000 to 20,000 yards, but as the tawny cordite and black smoke from the battle-cruisers and destroyers was drifting it was very hard to see more than two German ships at a time. The opposing battle-cruiser squadrons had now drawn a little apart owing to the zigzags and many alterations of course. There came a slackening in the fire; but a new and deadly weapon was being used, and the tracks of torpedoes could be seen rushing across the line of the British advance. Course was again altered, towards the enemy this time.

Sir David's orders to the destroyers were that they should take any favourable opportunity for an attack with torpedoes, and as there seemed to be some smoke and mist in the east, twelve of the British boats rushed ahead to take up a position of advantage. The German small craft, however, were not behindhand. A light cruiser with fifteen destroyers steamed out, and a spirited little action between the destroyers of both sides was soon in full swing at deadly close quarters. Two of the Germans were sunk, and the rush ahead still continued. Commander Bingham took Nestor right at the enemy battle-cruisers. He was followed by Nomad and Nicator. The shells falling in showers all about them, Nomad was so badly damaged that she fell out of line before she got in range, but the others gallantly rushed on and fired their torpedoes at the Germans, who were forced to turn away to avoid destruction. As the |

manoeuvred they blazed away with their lighter guns at the dauntless pair. Nestor was hit by a German light cruiser and brought to a standstill, while the battle surged onward. Later on, when the greater conflict once more overspread the scene of this opening fight, the German Battle Fleet in passing sank the intrepid and then lonely destroyer leader. She had continued to fire her torpedoes until not one was left. All Britain must rejoice that Commander Bingham, with the survivors of his dauntless crew, was rescued by the Germans, and that the Victoria Cross was afterwards received by the young hero. Nomad, the first of the destroyers to be disabled, was also sunk when the German Battle Fleet came upon the scene, but a considerable portion of her brave crew was saved and taken to Germany. Nicator, the third of the three little destroyers, got safely back out of the conflict in spite of shot and shell. Her captain throughout the engagement was leaning over the front of his bridge smoking a cigarette and whistling the latest popular tunes of the wardroom gramophone. He was giving directions to his coxswain by signs, zigzagging his way in and out and dodging the salvos like a three- quarter on a Rugby field. Both he and the captain of Nomad were afterwards awarded the D.S.O. Petard, Nerissa, Turbulent and Termagant, getting within 7,000 yards of the enemy, discharged their torpedoes. The desperate fight between the battle-cruisers was as fierce as ever. By this time many heavy shells, hitting continuously, began to tell their story. The third German ship was in flames, and it was noticed that the enemy's precision and rate of fire were not nearly so good as they had been. To protect themselves the Germans set up a smoke screen, altering course as soon as it had fairly hidden them. The enemy's salvos were still falling close together, and at this moment one of them crashing upon Queen Mary struck her abreast of Q turret. There was another tremendous explosion, and again a |

dreadful towering cloud of brown-grey-smoke mounted thousands of feet into the air. Tiger, which was in station two and a half cables astern, steamed right into the thick of this awful pall. There was no time to alter course. Falling fragments rained upon her decks in the darkness. Captain Pelly has stated that the column stood up solid like a wall. As the pall of smoke drifted northward the stern of Queen Mary stood high out of the sea, the propellers still turning and the water round boiling iiercely, for the between decks was a mass of flames. A skylight had been blown open aft, and up the hatch a great wind from below was whirling a column of papers high into the air. At this moment came a second explosion aft, and fragments were thrown in all directions. A midshipman in an after-turret stated that he felt the tremendous shock, and both the enormous 50-ton guns appeared to stand on end and sink breech-iirst into the ship. How he got out of the turret seems doubtful, but he found himself standing on the after-funnel, now lying flat upon the deck. Realising that it was a case for swimming, he took off his coat, and was stooping down to unlace his boots when there came a second explosion. He does not remember going up, but only the sensation of falling, falling, falling that is known so well in dreams. It ended in a splash as he arrived in the embrace of the North Sea. Out of all her splendid ship's company but eighteen survivors were picked up by a destroyer. At the beginning of the action our battle-cruisers were six to five, with 13.5 and 12-inch guns against the 12- and 11-inch guns of the enemy. Now they were but four to five. The thick armour on the German decks and the subdivision of the compartments had proved more effective than had ever been foreseen. All this time Commodore Goodenough, with his " City" class light cruisers, had been scouting far ahead of Admiral Beatty. At 7.38 he reported that he had sighted the German Battle Fleet in the south-east, and that they were steaming north. Sir David |

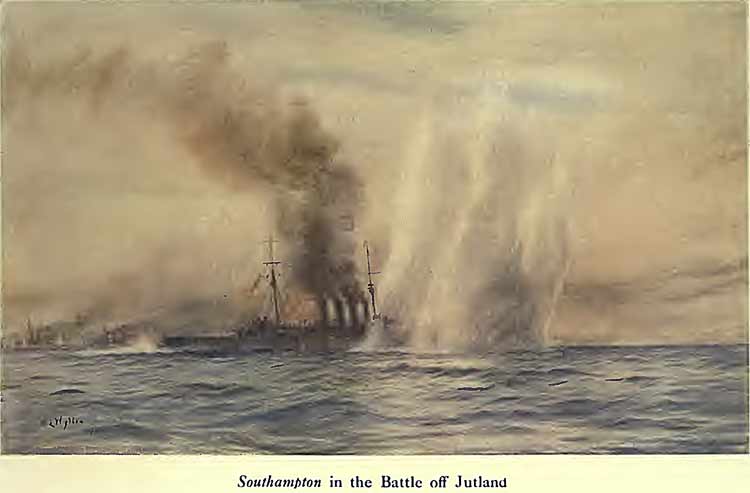

therefore called in his destroyers, and when he had himself seen the enemy coming up with the wind astern he turned his ships about, signalling to Admiral Evan Thomas to follow. When the German Admiral observed that the British ships were changing their direction he also made a sixteen-point turn, and thus the tide of the battle surged back towards the north-west, where Jellicoe was approaching in support. Meanwhile Commodore Goodenough determined to discover all he could of the disposition and number of the German Battle Fleet. He steamed under a very heavy fire to within 13,000 yards of the heavy ships. The drawing opposite page 120 shows Southampton at the moment when a German salvo was falling just clear of his bridge and forecastle. This is no fancy picture. It was enlarged from a tiny photograph taken at the moment, and though in the original the ship is little over half an inch long, one can see quite clearly how close together the German shells fell, and to what a prodigious height the spray was driven. The Commodore sent off many reports to his Admiral, all the while turning his little squadron now here now there in order to dodge those dreadful columns of spray which fell about him so continuously. Only skilful handling and wonderful luck saved the Second Light Cruiser Squadron from disaster. Moresby, which had stayed behind to help Engadine with her seaplane, now rejoined and made a spirited attack at 6,000 yards, two points before the enemy's beam. The four battleships of the "Queen Elizabeth" class had been from the first hampered by the smoke from so many ships drifting between their line and the enemy. The tremendous shells hurled by their mighty guns might have been expected to wreck the German battle-cruisers if only they could have scored a percentage of hits, but the tawny cordite clouds and the smoke screens all tended to make range-finding difficult and spotting almost impossible. Besides this the ships of Admiral Evan Thomas could not steam so fast as the battle-cruisers and tended to drop astem; the enemy were 20,000 yards away, and it was hard to see |

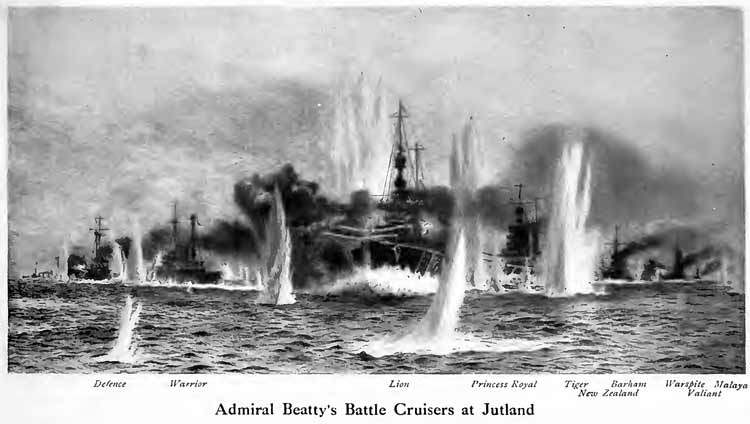

more than two ships at a time. The flagship Barham was first hit at 4.23, and about this time punishment was no doubt also inflicted on the enemy. After the sixteen-point tum the Fifth Battle Squadron was able to take a more important part in the offensive, and many hard knocks were given and received. Sir David's battle-cruisers, still in hot action, were now within an hour's steaming of Jellicoe's fleet, the two leading ships of the Fifth Battle Squadron, Barham and Valiant, were helping by firing upon the German battle-cruisers, while Warspite and Malaya were engaging the enemy's main fleet. The light cruiser Fearless, with the First Flotilla, was leading the whole fleet, and Champion, with the Thirteenth Destroyer Flotilla Squadron, had gone ahead of Admiral Evan Thomas's heavy ships. The First and Third Light Cruiser Squadrons were in position on Sir David's starboard bow, whilst Commodore Goodenough was on his port quarter. Clouds and smoke became very thick towards the enemy, who was running right before the wind. The mists behind him were variable, at times so dense that while at 14,000 yards the German ships were very indistinct, on the contrary the British showed up dark against the afternoon light. This enabled the German gunners to continue firing, even though the British Flagship and her consorts were sometimes obliged to stop owing to the haze. Lion a little later, owing to a slight improvement in the weather, got off some fifteen salvos, and at the same time her course was gradually altered towards the enemy, changing from N .N.E. to N.E. She was now approaching the Battle Fleet, and it was important that she should conform to the movements ordered by Sir John Jellicoe.

For a moment it is interesting here to break the narrative by giving the personal impressions of a midshipman who was in the fight. In a great sea battle only about a score of either oflicers or men see anything of the real progress, but if the reader can fancy himself a midshipman of a turret on board a battle-cruiser he will probably accept the following as a true experience : |

If you have Oldham and District items that we can include on our website, PLEASE visit the information page to find out how you can help.