JOHN KNIGHT by Jeremy Sutcliffe Background: An aristocratic land owning Britain, Rule by an unreformed and unrepresentative Parliament with a restricted wealth based electorate, an emerging Industrial Revolution, Revolution in America, Revolution in France. Into this maelstrom of ideas and events let’s introduce John Knight.

He is of interest, not just because of his local activism, but because of his longevity. He lived almost 80 years and was active through five decades of radical activism from the Jacobins inspired by Paine and the French Revolution, through to the early years of the Chartists He was born in either 1762 or 63 at Stonebreaks in Saddleworth, where his father owned the Neet Mill, a hand loom operation. After his father’s death, Knight and his brother run the mill, which fails, perhaps because of William’s death, perhaps because of the pressure of new techniques affecting handloom weavers. Knight’s frustrations about the lack of political rights is growing as is his own radical activity. He moves to Manchester and then Oldham setting himself up as a book seller and a dealer in radical literature, particularly promoting the ideology of Thomas Paine. In April 1794 he is involved in an incident that was to become known as “the Royton Races" A group, calling themselves “The Friends of Reform”, otherwise described as Jacobin reformers met in Royton, possibly on open land, where occasional horse races were held, (Royton CC still play at the Paddock) near the Light Horseman on Sandy Lane, to petition the King for the reform of Parliament. The Vicar of Royton incited a “Church and King” mob of 2000 from Oldham, supported by army recruits and possibly cavalry, broke up the meeting including storming the 'Light Horseman' to which the reformers retreated and a local woman, a child at the time, recalled Jacobins fleeing through her home to escape. Amongst those arrested was John Knight and brother William. In Oldham Church next Sunday a sermon was preached concluding with the, “From all sedition, privy conspiracy and rebellion, from all false doctrine, from battle murder and sudden death, Good lord deliver us.” After his arrest Knight was taken to the Lancashire Assizes. When the trial came up in 1795 he was acquitted, but he was now a marked man and he was soon to be imprisoned for two years following a seditious speech in Royton. The next reference relating to John Knight is that he was associated with the United Englishmen in 1801 but it wouldn’t be surprising if he hadn’t been involved earlier. The United Englishmen was an underground revolutionary society that existed in England between about 1796 and 1802 and which sought to overturn the government by means of a co-ordinated insurrection in England, Ireland, and Scotland. The foundations for the United Englishmen were laid after attempts to seek political reform through constitutional avenues were unsuccessful in the first half of the 1790s. Many English radicals, particularly in the northern manufacturing districts, were lured by the opportunity offered through the United movement (United Irishmen was well established) and the first cells of the United Englishmen were established in late 1796. It conducted its proceedings in secret and members guarded their identity through oaths and esoteric handshakes. Not Knight but three other Oldham members of a United Englishmen cell were arrested and sentenced to transportation for sedition. There seems nothing on Knight for the next ten years but in 1811 he is recorded as being the co-founder of a Political Reform Club in Manchester. In 1812 John Knight finds some notoriety as one of the “Manchester 38”, arrested by Joe Nadin for administering oaths to weavers pledging them to destroy steam looms and for a seditious meeting. Remember Knight was a hand loom weaver whose business had failed. He is now part of the Luddite movement. We have first hand accounts of this meeting and the arrest.

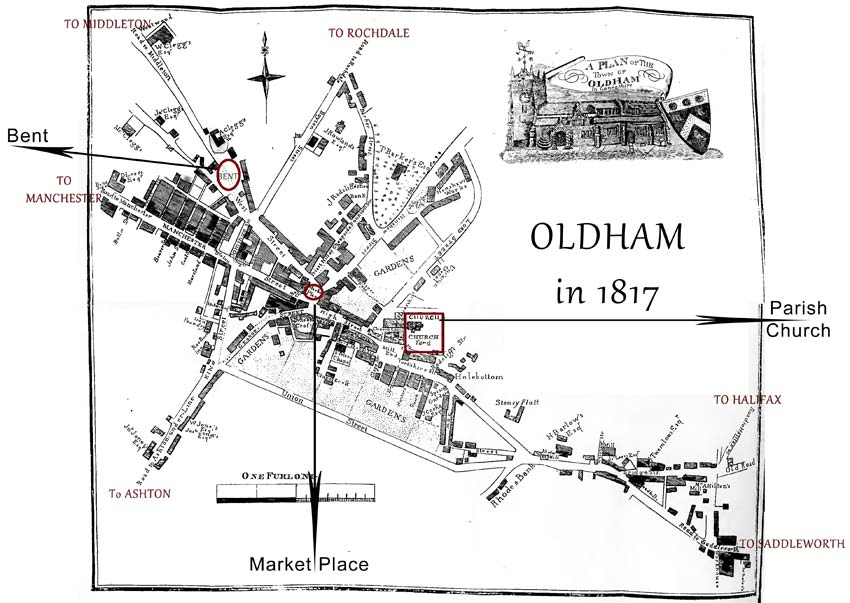

Knight was to spend the next 12 weeks in prison in Lancaster prior to trial but the trial collapsed when the evidence of a paid informer, Samuel Fleming, evidence was rebutted in court and the judge ordered the acquital of the “Manchester 38.” There is a celebratory dinner held in Manchester by the “Friends of Parliamentary Reform” attended by no less a person than Major John Cartwright who had established the Hampden club in London. Named after John Hampden, an English Civil War Parliamentary leader, they were intended to bring together middle class moderates and lower class radicals in the cause of parliamentary reform. Needless to say Hampden Clubs worried the authorities and Cartwright was arrested in 1813 for promoting them. While William Fitton of Royton is credited with setting up the first Hampden Club outside London, it is John Knight who is active in setting them up across south Lancashire. In Oldham it is called the Oldham Union Society but its prime purpose is to co-operate with the Hampden Club in London. Bent Green is the favourite meeting place in Oldham and the public house in which it meets is known as the Reformers School. But note, at that time the area round bent is probably the most populous part of Oldham

A first public meeting of Radicals is organized at Bent Green in September 1816 with a John Earnshaw in the chair. In 1817 a major demonstration is planned for Bent Green. Radicals from all around marched into town demanding both Paliamentary Reform and the repeal of the Corn Laws (The Corn Laws were measures enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846, which imposed restrictions and tariffs on imported grain. They were designed to keep grain prices high to favour domestic producers. The laws did indeed raise food prices and became the focus of opposition from urban groups who had far less political power than rural Britain. The Corn Laws imposed steep import duties, making it too expensive to import grain from abroad, even when food supplies were short.) To deal with the situation troops are mobilised and stationed on Fog Lane (King St) Nationally there is great nervousness on behalf of the establishment. Habeus Corpus is suspended. John Knight is one of the men targeted in the repression this allows. Bateson recounts that Knight was dragged out of bed in the dead of the night and carried off to London in chains. Although not cited as such, Knight was perhaps in the company of those arrested on March 30th 1817 and sent to London heavily ironed by the legs. Nadin wished to add body and kneck collars and armlets with chains but the King’s messengers objected to their use. Knight is imprisoned for ten to eleven months without trial (some sources say in Salisbury and Worcester, others London) eventually he is released and has only 5gns to assist him to get the 160 mile back home. But by 1818 he’s back in the Oldham area once again co-ordinating the Hampden Clubs. He becomes known as the Major Cartwright of the North. In these times, Bateson tells us, the Oldham Radicals met in secret conclave under the shadow of arrest, gathering at “muffin aetings” in Bent and Glodwick eating muffins and cheese and drinking beer while the latest publication of the radical William Cobbet was read out. In 1819 Knight can be regarded as one of the key organisers of the meeting to be held at St Peter’s Fields. He has wanted Cartwright to attend but he is now too frail and Henry Hunt becomes the prime speaker. Knight leads the Oldham contingent down to Manchester and is on the platform at the rally. He is also named as one to be arrested but in the chaos he escapes. He is however eventually arrested at home and for his involvement in this and a meeting in Burnley in November 1819 he finds himself in Lancaster Jail. Interestingly, he is acquitted of activity at Peterloo but is guilty of sedition in Burnley. Jail didn’t quieten him. He continued his campaigning in letters to the Manchester Observer. In 1820 he also petitions the King, unsuccessfully, to be exiled to America. During the 1820s and 1830s he continues his political activity in Oldham. He is often toasted and fêted at dinners for services to radicalism.

He is active in all aspects of reform movement be it expansion of trade unions, something called exclusive dealing, the reform agitation of 1832, anti-poor law protests and agitation against the Corn Laws. Sometime in this period he becomes the Secretary of the “Oldham Political Association” supporting radicals such as Henry Hunt, John Fielden, John Doherty and Fergus O’Connor. In 1827 he is the lead speaker at Bent Grange to petition parliament for free import of foreign grain, annual parliaments, universal suffrage, election by ballot ... issues anticipating the demands of the Chartists of the 1840s. In 1830 he becomes the secretary of the National Spinners Union which had operated since1796 disguised as a friendly society: “Friendly Associated Cotton Spinners of Oldham and Neighbourhood” (but with secret rules) Also in 1830 there is a requisition by 300 Oldham Households appealing for repeal of the Corn Laws and, according to Butterworth,

But by now the key issue nationally is the issue of electoral reform and one that brings a constitutional crisis with the peers and bishops of the Lords blocking it almost bringing the country to the verge of revolution In 1831 John Knight achieved notoriety amid the turmoil. He posts on the walls of the Constable of Oldham “a handbill of an inflammatory character attacking the Bishops and the Peers for their opposition to the Reform Bill.” 1831 November John Knight calls a meeting at the 'Grapes' to form Radical Union. A week later an additional 100 special constables are added to local force anticipating riot In 1832 the Peers give way and Parliamentary Reform is carried at the second attempt and in the second act Oldham is included as a parliamentary borough with two MPs. There is the ringing of church bells and the firing of cannon. But of course it is nowhere near universal suffrage

So, in the General Election of 1832 Oldham elects its first two MPs on the site of what was to be the Town Hall with bands and 15,000 observers present. The radicals William Cobbet and John Fielden having been asked to stand, the result is a Radical landslide Cobbett 677 Of the election Cobbet was to say,

Perhaps. Remember John Knight's Oldham Political Association. During the election of 1832 its tactics include:

In December 1833 Knight becomes a leading member of the Oldham branch of the “Society for the Promotion of National Regeneration” which had been formed by trade union advocate John Doherty and co-operative movement father figure Robert Owen to campaign for fairer working hours and conditions for factory workers. John Fielden MP is a leading advocate. The same month sees a mass meeting held behind the Albion where a “violent republican” called Lomax argued that eight hours a day labour was sufficient to provide for everybody. In 1834 there is public disturbance following a demonstration by the “Ancient Virgins” (The Oldham “Union of Women Workers”) on behalf of the 8 hour day. April 1834 also sees a strike in Oldham by 12000 workers and a major disturbance on April 15th results in the effective military occupation of the town. In September Knight is reported as railing against the status quo in a speech:

As the Chartist movement emerges in the mid 1830s Knight appears to side with the faction associated with Fergus O’Connor but the Radical movement is beginning to split on the method of approach. Knight backs O’Connor to replace Cobbett after Cobbet's death in 1835 while Fielden supports Cobbet’s son. It would appear that O’ Connor’s candidacy splits the Radical vote and a Tory candidate wins the seat. [I would need to do more reading around this] In 1838 Knight becomes an agent for O’Connor’s successful Chartist newspaper the “Northern Star” and in July 1838 Knight is quoted as making a speech complaining that,

Radical and active to the end, Knight chairs a meeting five days before his death at his home on Lord St on September 5th 1838. His funeral followed on September 9th. Two thousand five hundred friends, relatives and Owenite Socialists, accompanied by a local band marched eight abreast to his burial at St George’s Church in Mossley, possibly the family grave, and a funeral oration is preached at the Socialist Institurte in Oldham on September 17th. |