A Gartside Sent to Van Diemen's Land - "Man's Inhumanity to Man" This Narrative and pictures started life as an illustrated talk, for the local Family & Local History Societies. Its first 'outing' should have been in Shaw & Crompton, on the 26th March, 2020 ... the week after the whole country went into 'lockdown' as a result of the Coronavirus Pandemic. Like many others, I turned to the internet to tell my ancestor, Edwin's story ... |

|

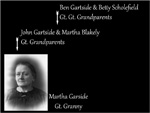

The Gartside family name (with or without the 't') originated in Saddleworth around the 1300s and, even as late as the 1841 census (with or without the 't'), was found almost exclusively in Lancashire and the West Riding. This is a double-edged sword for the family history researcher, as searches can be concentrated in one area but, on the other hand, many babies with the same forename were baptised within months or even days of one another in the same local churches. According to Ammon Wrigley, in 'The Wind Among the Heather', the Gartside family name was first recorded as 'de Garthside' in the 1300s; Garthside being a hamlet near Milnrow at that time. It's first apearance in Saddleworth was in Denshaw, in the late 15th century, when Roger Gartside of Rochdale, gentleman, became the owner of the 'Darkside' of Friarmere. When I started researching this branch of the family, about 12 years or so, ago, I knew with certainty that I had the correct line going back from my own grandmother to my 3 times Great-grandparents BEN Gartside and BETTY Scholefield. In the early days of the research, I'd wasted much time and effort, following a wrong assumption that fitted perfectly (or so it seemed!) but which turned out to be quite wrong when I dug a little deeper. I didn't want to make the same mistake ever again! Extra vigilance in the search would be absolutely necessary! Many family trees that I came across on-line recorded BEN as the son of John Gartside and Susannah Barker. This couple did have a son 'Ben', baptised on the 1788/08/30 recorded as ... chr. of 'Ben' at St Chad, Saddleworth; "son of John Gartside and Susannah; yeoman; Castleshaw". This fitted with BEN's known age; there were no burials or other marriages that might have been him; and it was the right area of Saddleworth. It was easy to believe, and agree, that BEN was their son as there were no others that appeared to fit the bill. However, John and Susannah were obviously substantial members of the Gartside family but my BEN was a clothier (or weaver) and his family were obviously not at all affluent. BEN's putative father, John, died in 1812, so I went to Preston to look at his will. It ran to many pages and he mentioned children (both alive, and dead but with descendants), grandchildren and sons-in-law, amongst his many bequests. He was a man with a wide number of business interests and possessions but there was no mention of son 'Ben', at all. I was sure that he would have been mentioned, if only to deny him any part of the inheritance, if he was still alive. I returned to the old Parish Records to see what I'd missed. The baptisms at St Thomas, Friarmere (Heights Chapel) and some of the Non-Conformist Chapels were not available on the usual births & marriages internet sites, at the time, so it was back to the Local Studies Library and trawling through Parish Records on the film readers; and I had my 'Eureka moment!' He was there! Baptised at St Thomas, Friarmere (Heights Chapel). BEN was baptised in 1789 on Jun 7th; his father was recorded as John Gartside, his mother as Hannah and his birthplace as Castleshaw. Plus factors were his lowly station in life, his birthdate, his birthplace (the same as his home when his own children were baptised); BEN's mother's maiden name was Lees and his own second daughter, Betty, was baptised with 'Lees' as her middle name; a later daughter was baptised as 'Hannah Lees Gartside'. Trying to go back another generation to find JOHN's father was more difficult. There are those records that fit known facts but other records, telling a different story, might have been lost or not even existed. There is just one that I feel is 'the one' ... but have no proof so won't include him! So, the first Gartside that I can, almost, and with fingers crossed, claim as an ancestor, is JOHN Gartside who married HANNAH Lees in December 1781, at St.Chad's, Saddleworth. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries the Gartside families in Saddleworth were pretty numerous ... as well as being spread up and down the social ladder from families who were poor weavers and labourers to those owning land, mills, mines and even, by 1830, a brewery! Needless to say, my own Gartside 'twig' was in amongst the poor weavers. JOHN Gartside had 7 children in the 19 years of his marriage, until his death, aged 44, in 1800. BEN was his 3rd child. JOHN's widow, HANNAH, would marry again in 1807, this time to Jesse Reynolds with whom she had 2 daughters. I only mention this because these family connections help to identify the family with more certainty in later records. BEN, a clothier (a weaver) of Bleakhey Nook, Castleshaw, married BETTY Scholefield in February1812, at St Chad's in Saddleworth and their first child, born in December 1812, was the Edwin of our story. So ... what is my own connection? Edwin Gartside was my 3x great-uncle, on my father's side. |

|

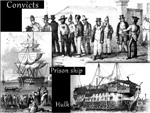

I started this research with just the name of an ancestor, Edwin Gartside, and this talk would be his story but, as always happens, at least with me it does, I find myself distracted into going down related paths.I could write pages about the prison ships, the Hulks, as they were known; or more pages about the transport ships, and the conditions which convicts endured, for voyages lasting 4 or 5 months. I could write endless pages, just about the history of the effects of British colonisation, on the indigenous people of Van Diemen's land! You'll be relieved to know, that none of that will happen! And here and now, I'm also going to apologise for the fact that I make virtually no mention of women convicts transported. Theirs is a whole different story which I shall leave to your own imagination or research. This story will only touch briefly, on the history that provides the necessary context, for Edwin's story. |

|

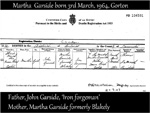

To start off, the first Gartside mention that I came across, when tracing my family tree, was my father's grandmother, MARTHA Garside, who was born in Gorton on March 3rd in 1864. |

|

MARTHA was the 9th of the 10 children of JOHN Gartside, who was born in Bleak Hey Nook, Saddleworth, in April 1821. JOHN, in his turn, had been the 5th of the 12 children born to BEN Gartside and wife BETTY, nee Scholefield, who were married at St. Chad's, Uppermill in 1812. The Edwin of our story was JOHN's eldest brother, born in December 1812, and baptised in January 1813. |

|

In the years before BEN and BETTY married and before Edwin's birth, the area was mainly one of uncultivated moorland with 'islands' of cultivated fields around small farms and hamlets. Bleak Hey Nook, home of our own Gartside family, was mainly a hamlet of woollen weavers (clothiers as they were often described) working from their own homes in what was once a well respected, relatively well-paid, occupation until weaving began to become mechanised and the weavers started to gravitate towards the new mills. It was a slow, reluctant change leading to ever-increasing hardship, and poverty for the handloom weavers, as faster production in the mills meant cheaper cloth. Heights Chapel (St. Thomas'), in Friarmere was the church of choice for many of these old Gartside families. |

|

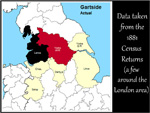

Even as late as the 1841 census, the name Gartside (with or without the middle 't'), was found almost exclusively in Lancashire and the West Riding. This distribution map is constructed from data on the 1881 census, showing the cluster of Gartside names ... black indicating the highest number. As mentioned, earlier, this is a double-edged sword for the family history researcher, as searches can be concentrated in one area but, on the other hand, many babies, with the same forename, were baptised within months or even days of one another, and in the same local churches. |

|

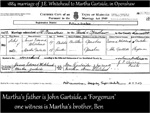

When I started researching this family branch about 12 years ago, I only knew, with certainty, that I had the correct line going back through my father as far as my great-grandmother, MARTHA Garside. In the earliest days of the research, I'd wasted much time and effort following an assumption, which fitted perfectly but which turned out to be completely wrong when I 'dug' a little more carefully! A routine confirmation, as I thought, was to send for the marriage certificate for MARTHA, to my great-grandfather, in 1884. It gave me her own father's name as JOHN, which I hadn't expected! And a brother Ben, as witness. A rather large branch of my family tree fell off and 'bit the dust'! I didn't want to make the same mistake ever again! Extra vigilance in the search would be my mantra! |

|

So, next came the search for MARTHA's birth, her mother's maiden name, and the family's presence in the census returns. Her birth certificate confirmed her father's name and also gave me her mother's name before marriage ... Martha Blakeley. The Parish record for the marriage of JOHN and MARTHA Blakely in 1843 provided me with the name of JOHN's father, BENJAMIN. |

|

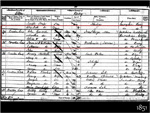

From census returns for the family, I knew that JOHN had been born in Saddleworth but, in the years that followed, he had moved around quite a lot. Working forward in time, from MARTHA'S birth in 1864, then backwards, I knew that in 1851 he was in Elton, Bury.

In 1861 he was in Gorton ... with his ever-growing family; in 1871 he was in Openshaw; in 1881 he was in Droylsden; |

|

and in 1891 he was in Gorton again ... where he died in 1892. From these returns I also had the names of 9 of MARTHA's siblings. How did I know it was always the same family? JOHN was consistent on the census returns; his age always tallied; his place of birth was consistently Saddleworth; he was always in the same occupation, as a foundry worker. His children could always be identified with certainty as several were born in dfferent locatiions, which always matched up. |

|

My next job was to find JOHN on the 1841 census. For this, I had to rely on putting together as many coincidental links as I could find, and it was here that I did have some luck. From the Parish Records of his marriage in 1843 I had his address, on Booth Street, in Salford and also that of wife-to-be MARTHA; they were only doors apart. On the 1841 census JOHN was in Salford, an iron forger, unmarried and living in lodgings, on that same Booth Street. The only thing that gave me pause was that he gave a 'Yes' to having been born in the county of Lancashire. But, as everything else fell into place, I accepted that he might just have wanted to fit in, with the others in his lodgings. After all, I had evidence of even bigger lies on my own mother's marriage certificate!! |

|

Now I needed a little bit more luck. How could I tie him back to his own family in Saddleworth? There were too many 'Johns' around the same age! Fortuitously, there was a family sampler, handed down through the male line, of JOHN's family, and stitched after the death of his parents. His father, BEN, died in 1845 and his wife was named as BETTY. I started looking for Saddleworth marriages for a BEN & BETTY around the right date and then, having found them, a search for baptisms of their own children. Again, consistency in BEN's occupation as a 'clothier' and the fact that they came from a small hamlet, Bleak Hey Nook, made this relatively straightforward. |

|

BEN, a clothier, of Bleakhey Nook, Castleshaw had married BETTY Scholefield in February1812, at St Chad's in Saddleworth, and the first of their 12 children was born in December 1812, and he was the EDWIN of our story. Anyone, who knows me, knows that for years I have had a passionte interest in Peterloo. In 1891, BEN, as a 30 year old weaver, was living in Saddleworth from which a strong contingent of reformers marched to Manchester on that fateful day, Monday 16th August 1819. It's not difficult to imagine that BEN would have been amongst the men who walked all those miles to attend the meeting, and hear Henry Hunt speak, about the necessity for Reform. Would BETTY have gone with him? I think, probably 'not'. Baby Lucy had been born in May of that year and BETTY already had 3 other young children to care for. However, the eldest, Edwin, would have been almost 7 years old and might have accompanied his dad. |

|

My 2x Great-grandfather, JOHN, was the second son, born in 1821, following the birth of sisters, Mary (1814) , Betty Lees (1816) and Lucy (1819). BEN & BETTY would have a further 4 children, Frances (1823), Charles (1825), Ben (1827) and Alfred (1831) whilst still living in Bleak Hey Nook and BEN remaining a clothier. At some time between 1831 and 1833, the family moved out of Saddleworth to live in Oldham. How do I know that? Because the next 3 children Hannah Lees (1833), Sara Ann (circa 1835), and Frederick (1836 but died in 1837) were born in Oldham. Their mother, BETTY, died in 1839 age 48 (according to a family sampler). |

|

Most of the family are found on the 1841 census, living together on Soho Street, Above Town, in Oldham. Widowed BEN was still recorded as a clothier. But my JOHN, as I expected, was one of the siblings not on the census with them! How could I prove, to my own satisfaction, that my JOHN was, in fact, the missing JOHN from this family? Was the family sampler proof enough? This was a tricky one! In 1841 there were several 'Johns', around the same age, living in and around Saddleworth, Oldham and Ashton, several of whom were living in lodgings, and not with family but, importantly, none was a foundry worker. |

|

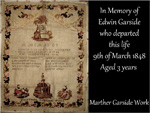

Still convinced that this Oldham family was my JOHN's family, I then researched the siblings, after 1841, and this was where I had another stroke of luck. Several of the siblings were found living very near to JOHN, on several census returns, as were a couple of his nephews. The clincher, for me, was that JOHN & MARTHA's own first child, a boy, died in infancy and yet another sampler was stitched, naming their lost son, 'Edwin'. Three daughters followed; the fifth child was a boy who would also be baptised as Edwin. JOHN's sister, Lucy, and his son Ben, both had sons who were baptised as 'Edwin'. Edwin, as a name, was practically unknown in the local Gartside families, at that time so, I thought, could they have been named for JOHN's elder brother? But for what reason? Was he lost to them in some way? He hadn't been found in any of the census searches I'd done. Had he died? Emigrated? Joined the army and was always overseas? |

|

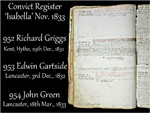

My next stroke of luck came when I found an Edwin Gartside was in the criminal registers on Ancestry.

This is the entry book for court costs for prosecutions, in this case, felony. But was it my Edwin? As already mentioned 'Edwin', as a Gartside name, was pretty rare. Searching the records for an Edwin born around 1813 only threw up 3 results over a period of 20 years. The other two were found on later census returns. So ... my Edwin was a criminal! He had been charged and sentenced at the Quarter Sessions, in December 1832. But what had he done, and where had he disppeared to? |

|

Over the intervening years I pieced together his sad story. Always, in my imagination, I pictured an excited little boy, perched on his father's shoulders, on the long walk to Manchester, in August 1819. And then, I imagine the story darkening as this child sees the yeomanry, with sabres held high and flashing in the sunlight, as they rode into the throng on St Peter's Field, slashing at the people on all sides. And then, there'd be the long, sad walk back home, with the wounded, who limped and sobbed, alongside them. The scenario would be real enough; but BEN and Edwin's part in it? That really is [probably!], just in my imagination. |

|

Life in the Oldham of 1831/'32, in which Edwin would spend at least 18 months, would have been very different from that with which he would have been familiar in the rural areas of Saddleworth. Wages for a labourer were low and hours would be 12 to 14 hours a day; sanitation and running water were virtually unheard of, in workers' homes; privies were emptied infrequently; TB and other infectious and killer diseases could run through crowded urban communities unchecked. Given his circumstances, it's highly likely that Edwin was illiterate and never had any opportunities for an education. |

|

Political activism in Oldham hadn't disappeared after Peterloo, but tactics had changed. We can read, in Hartley Bateson's 'History of Oldham' that,

continuing again :

and, he continues:

this was probably a very sanitised version of the serious unrest in Oldham leading up to the Reform Act. |

|

Bateson continues, again :

|

|

In June 1832, the long-awaited 'Great Reform of Parliament' and the extension of the franchise (although disappointingly limited) was, very reluctantly, passed in the Lords at the third attempt. The new Act gave Oldham the right to elect 2 MPs in the newly reformed Parliament and, in the December, there would be another General Election. At the prospect, Oldham was in a state of great excitement and hope for a better future. Amongst the Oldham candidates were the radicals William Cobbett and John Fielden, both of whom would be elected. Can we imagine Edwin taking any part in these proceedings or any of his family members, come to that? Or, was he too busy enjoying different thrills and excitement, in the company of other young men of his own age? All we know for sure is that, within weeks, he was in serious trouble in the courts. |

|

By early 1832, the year in which he was charged, 19 year old Edwin would have been living in Oldham and almost certainly with the family. In the criminal records, we can find that on the 3rd of December, 1832, at the Salford Hundred, Michaelmas Quarter Sessions,19 year old Edwin Gartside was sentenced to 7 years transportation, after being found guilty on a charge of larceny. So ... the first thing to find out was, what exactly had he done? When and Where? |

|

Rowbottom's Diary concludes in 1830 so, unfortunately, that wasn't going to provide any answers. The next source I turned to was Edwin Butterworth. In the Local Studies and Archives Library are transcripts of Butterworth's 'Register of Oldham News and Reports' which include cover of 1832. If he was sentenced in December then I could work backwards from the trial date and see what I found. I didn't have far to go back. In November, under the stark heading of 'FELONIES', I read :

Intrigued, as to whether or not Edwin had been in trouble before, I carried on, working backwards. in June, there was mention of a 'Gartside' being caught attempting to break into the 'Old Fox' public house, on Henshaw Street. Edwin again? I found no mention of another committal. |

|

The Prosecutor's Bill for Salford Quarter Session, in December 1832, includes an entry under Edwin's name, for "felony - stealing and receiving'. |

|

The judgement and sentencing reads :

So now I knew ... but that was harsh! |

|

By mid January, Edwin was on his way to the Prison Hulks, at Chatham, on the River Medway, with the shipyard nearby. The 'Cumberland', in Edwin's case, was his destination. He would remain there until he was transported, in July 1833, aboard the 'Isabella' bound for Van Diemen's land. The Hulks were old warships, no longer fit for active service and were notoriously vile and dangerous. They were used for those serving shorter jail sentences and for convicts en route to be transported. Until the American War of Independence, some prisoners had been transported to the American Colonies thereby, at one stroke, ridding the country of 'Undesirables (both political and criminal) and saving the cost of maintaining convicts in jails. With the loss of the American colonies, in the mid 18th century, the situation became desperate. The answer came with the opening up of British colonies in Australia's New South Wales and then in Van Diemen's Land. During the Napoleonic Wars the hulks had been used to hold French Prisoners of War. After the end of the war with France, in 1815, and with the costs of the war still to be met, there was no money available to build more jails so the hulks were used again, as jails for those serving shorter term prison sentences and for convicts awaiting transportation. |

|

Life on the Hulks was generally considered to be 'hell on earth'. Once the prisoners arrrived at Chatham they would have been given a prison uniform of coarse trousers and jacket. They would also have leg irons fitted. A typical daily routine at Chatham might be along the lines of: 5:30 am Convicts would be called to muster on deck which would be followed by a breakfast of thick gruel and bread. Hammocks would be brought up to be stowed on deck. The prisoners would then be put into boats to take them ashore for work. Once on shore, they would be divided into groups, in the charge of a dockyard overseer. The work would involve hard labour such as construction work, building, general repairs and maintenance, rope-making and so on. All of this would be under the watchful eye of armed guards. At 12 noon they would return to the hulk for dinner and another muster. At 1:20 they would go back to work on shore until their return at 5:45. The evening meal would be gruel or a piece of meat or cheese and an allowance of small beer (ie. weak in alcohol content). At 7:30 The day finished with another muster and prayers. Following this, they were locked up for the night in tiny cells of multiple occupancy. Unsupervised, it was lawless below decks, even when fighting, yelling or screaming was heard. Saturday evening finished with a wash and shave, making ready for Sunday and a service in Chapel. Visitors were family only, and allowed about once every 3 months, on a Sunday. Punishments, for any misdemeanours, were harsh, including 50 lashes, ration restrictions, solitary confinement, and double irons. Disease was rife and scurvy common. When Edwin was held there, horrific as it was, almost unbelievably, it had been far worse in earlier years with a high percentage of deaths. |

|

On the 28th of July, 1833, after 6 months in the 'Cumberland', Edwin, one of 300 convicts, sailed from Plymouth, on the 'Isabella,' for the 4 months voyage to Van Diemen's Land, where he arrived on the 13th of November. Transportation was considered good value for money, by the government. The cost of transportation was about £20 per man in 1830 but, taken against the cost of keeping a convict in prison in Britain, for 7 or 14 years, this made admirable sense. It would only cost about £1 a year in the colonies as most of the costs would be met by the 'masters' to whom the convicts were assigned. An extra bonus for the government, was the notion that all 'undesirables', political or criminal, could be transported, never to return. It was estimated that only 5% made their way back to England, after they had served their sentence. One reason, of course, would have been that they had to pay for their own passage home. However, what doesn't seem to have been taken into account was the heavy expense, of maintaining military garrisons, to control the convicts. Only a couple of years before Edwin was transported, the chances of surviving the voyage had increased dramatically, as a result of the newly appointed surgeon-superintendants who would be in charge of stores, and a medical officer on board the ship. We can compare the following two accounts: |

|

'The Transportation of Convicts, after 1783', written in 1923 by James E. Gillespie, gives an account of transportation in the first 2 or 3 decades of the 19th century and he writes :

"From the commencement of the convict's journey to Australia, he was subject to evil influences. Youthful criminals and those whose crime was slight were thrown into close association with the most vicious and hardened characters. To prevent mutiny on shipboard, guards were placed on the deck and at the gangway, but this was all the control or regulation to which convicts were subject. The mental horror of such a journey, where two or three hundred beings were stowed in the hold of a transport for four months, with nothing to do but to strive to eliminate all reflection can be imagined. The whole voyage was passed in gambling, in singing indecent songs and in every species of vice. A school was thus provided by criminals of the greatest experience. A man was valued according to the amount and adroitness of his villainies. Almost all their conversation was of the larcenous kind consisting of details of their various robberies and the singular adventures they had passed through." |

|

In contrast, in an assessment of his work as a surgeon-superintendant, Colin Arrott Browning, writes of his appointment as such, in 1831, and his subsequent attempts to ensure a good conduct-survival rate and institute education programmes etc. His book, 'England's Exiles', published in 1842, makes it appear that great improvements had been made but, how quickly or how far these guide lines were implemented, in other ships with other superintendant-surgeons, is not examined. Briefly, Browning selected a number of prisoners and to each, as a 'Captain', he would allocate a number of convicts, as a division. There would be other convicts, under the 'Captain's' orders, who would have specific reponsibilities, ranging from being in charge of the boys on board to discipline, cooking, barbering, clerical work etc. And there would be schooling. A daily routine, for every recurring 7 days, was established and the incentive for the remaining convicts was that their leg-irons would be removed, as soon as possible, if they co-operated. |

|

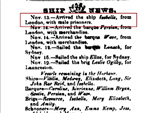

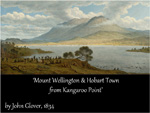

Nothing changes overnight so it's more than likely that Edwin's own experience, was somewhere, between the old ways and the new, during the transitional period. However, this news article in the 'Hobart Journal', dated 19th November, tells us that the 'Isabella' docked in Hobart, in November 1833, with her 300 convicts on board, including Edwin. In another article, it is mentioned that all convicts had survived the voyage. |

|

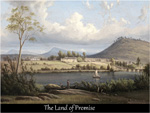

The island itself is in almost 2 parts astride a geographical line running from north to south. West of the line is a dense, rainforest-like landscape with almost daily rainfall. Habitation in the west was only really possible, along the coastline. To the east, and in the more central areas, there were more open plains, much of which had been created by the aboriginals annually burning off the scrub to create the necessary hunting grounds for kangaroo and wallaby etc. Unfortunately, this also provided ideal conditions for the settlers who applied for, and received, land grants on these traditional hunting grounds. When I was looking at the maps, and reading the contemporary published accounts describing the terrain, I couldn't really imagine it clearly. Looking for some illustrations, I came across a David Attenborough documentary, on the BBC, about Tasmania. It showed the almost jaw-dropping grandeur and beauty of the island, so much of which was completely unchanged by man. If the opportunity ever comes round again, to see it, you'll understand what I mean. It's mainly mountainous, covered with tall forests and thick, impenetrable scrub and vegetation, making much of it it too difficult for early settlement. To top it all, there is a stunningly beautiful coastline. |

|

40 odd thousand years ago, Van Diemen's Land was connected to Australia by a land bridge, across which the first Aboriginals walked. Rising sea levels eventually covered the land bridge and, for around 10,000 years, the Aboriginal Tasmanians were isolated, from the rest of the world until 1642 when the existence of the island became known to the Dutch explorer, Abel Tasman. Over 100 years later, in 1772, a French explorer visited the island then, in 1773, an English explorer and, finally, Captain Cook in 1777. Itinerant European sealers and whalers were working from temporary island bases from around 1798. |

|

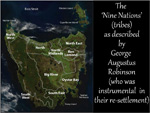

At the turn of the century (18th to 19th), the indigenous population was variously estimated as numbering between 3,000 and 10,000 and distributed across the 9 separate 'nations' or tribes. They were described as such by George Augustus Robinson who was ultimtely responsible for their final and fatal re-settlement. Some of the early explorers are known to have landed, and even had brief contact with the Aboriginal people. However, there was no official attempt to settle Van Diemen's Land, by any country, until 1803 when Britain decided to annex the island for herself by establishing a tiny military outpost, with 24 convicts, at Risdon Cove. That settlement quickly proved to be unsuitable and was relocated to what is now Hobart. |

|

From this Appendix, from 'Early Tasmania', by James Backhouse Walker, published in 1902, we can learn that, by 1804 there were 433 inhabitants in the colony, of whom 18 were in the civil department, 48 in the military, 279 were convicts, and just 13 were free settlers On the next page of the Appendix we can see the deployment of convict labour in the settlement, in 1804. There was a mix of artisans and labourers : 35 were working on the land and with animals; 76 were doing building work, including masons, sawyers, carpenters, blacksmiths, armourers, bricklayers, plasterers, lime and charcoal burners, etc.; and 4 were building ships. Further down the page we can see the variety of other employment to which the convicts could be assigned ... including clerks, taking care of government buildings, stores and gardens; boat crews; a gang of town labourers; and a night watch.There were bellringers, barbers, tailors, shoemakers, a printer, thatchers, a toolhelver, a cook, a baker and two drummers for the military. Plus, 32 were described as general servants. By 1806, the Europeans in the settlement, who had been left to fend for themselves, were struggling and on the brink of starvation. However, more settlers and convicts continued to arrive and, despite the problems, gained a firm foothold so that, by 1819, the Aboriginal and British populations numbered about 5,000 of each. |

|

Free settlers began arriving in large numbers from 1820 onwards, attracted by promises of land grants and free convict labour. From 1826, settlement in the island's north-west would be monopolised by the recently formed Van Diemen's Land Company. The traditional hunting grounds of the aboriginals was just the sort of land the settlers needed for farming and rearing livestock. As they settled their land grants and pushed the indigenous population into areas that couldn't support their nomadic, hunter life-style, hostility intensified and conflicts became more aggressive. |

|

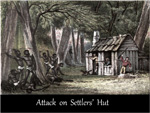

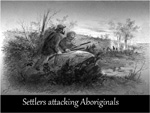

Relations between the aboriginals and the settlers were strained almost from the beginning, and most published illustrations and accounts were biased, emphasising that the aboriginals were the most likely aggressors although records tend to show a different story. For any transgression against the settlers, the retaliatory action was always greater and aboriginal deaths and injuries far higher than any suffered by the settlers. A number of incidents have now been classified as a 'massacre' because of the initial intent to murder the aboriginal folk. |

|

Depending on which contemporary account you read, we are given to understand that the aboriginals took every opportunity to attack the settlers. murder them without mercy and deserved nothing but the harshest penalties and that it was the settlers' right to abuse, hunt and murder them with impunity. Alternatively, the more reasonable accounts relate that, when the aboriginals attacked settlers, it was often in retaliation for such brutal acts as rape and the abduction of children and women. The subsequent revenge, on the part of the settlers was even more brutal and costly for the tribes. |

|

The rapid colonisation transformed traditional kangaroo hunting grounds into farms for growing crops and keeping livestock, resulting in the appearance of fences, hedges and stone walls. In effect, this left the indigenous tribespeople without the means to hunt for their own food. The situation was exacerbated, in those years, by numbers of escaped convicts, known as 'bushrangers,' who viciously and mecilessly preyed on both settlers and aboriginals alike. |

|

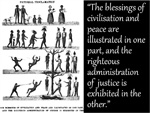

The government's public stance was that there should be even-handed justice ... but that was never going to happen. The settlers were rarely, if ever, executed ... always the aboriginal. In1826, a proclamation had been issued, in pictorial form, so that no-one could pretend not to understand it, which purported to state that penalties, for attacks or crimes, would be treated in the same way whether or not the perpetrator was a settler or an aboriginal. It didn't work, and what became known as the 'Black War' gathered momentum from 1828. |

|

The 'Black War', between 1828 and 1832, refers to a period of intermittent but frequent conflict between the British colonists, whalers and sealers, and the Aboriginal people. By some modern historians, it is described as genocide resulting in the elimination of the full-blood Tasmanian Aboriginal population. In November 1828, Governor Arthur had declared martial law, giving soldiers the right to shoot, on sight, any Aboriginal in the Settled Districts. It would remain in force for more than three years. In the so-named 'Black War', the official attitude changed and it became open government policy that the swiftly decreasing numbers, of indigenous aboriginal men, women and children, who still remained, should be forcibly re-settled in places where they could not impinge on the activities of the white settlers or be perceived as a threat. In 1830, the first attempts had been to herd them together and then pen them on the narrow Tasman peninsula but, like smoke, they had disappeared, escaping, despite the watchful eyes of their captors. |

|

Then, in 1832, with total aboriginal numbers then down to around 300, they were to be isolated without means of escape, on inhospitable islands. They were tricked into accepting the proposals by promises of a better future and an eventual return to their homelands. The first island to be considered proved unsatisfactory. There was no space for the men to hunt, or move around in their nomadic ways; and the people were dying in increasing numbers. Flinders island, in the Bass Straits, between Van Diemen's and Australia became their next 'new' home. It was an island where conditions for survival were, again, very poor. |

|

In 1847, when only 47 Aboriginal tribespeople still remained alive, they were again uprooted, and this time sent to Oyster Cove, in the extreme south-east, where most of them would stay until the end of their lives. No wonder that, as a people, they lost the will to live. |

|

Returning to the convicts ... they were brought on-shore in Hobart. They would have been in irons as even on this far distant island, convicts escaping was an ever present possibility. Most escapees would be recaptured; a few would survive for a time in the hostile environment, joining one of the gangs of notorious 'bushrangers'. Others would meet their death in the inhospitable terrain and a tiny, tiny few would be lucky enough to reach the coast and find a ship to get away from the island. |

|

Van Diemen's Land was variously described as a 'Hell Hole', the 'Botany Bay of Botany Bays', and a place for 'the most felonious of felons'. The smallest transgressions against authority resulted in excessively severe punishments. These included flogging with the 'cat', which was common; imprisonment in coffin-like chambers, without room to move or stand up; hard labour on the chain gang; limited diets; transfer to even harsher penal settlements, such as Port Arthur, with other '2nd time offenders'; and then more. One account states that conditions could be so bad that convicts would sometimes commit a murder, any murder, just to escape by being tried and executed. |

|

To try and give any sort of comprehensive description, of what a convict could expect, experience or suffer, would take hours, and prove too harrowing to read. However, when I was doing the research for this article, I came across an image, on the Tasmanian Libraries website, showing a page from a convict's notebook, in 1823. It was a crude drawing depicting the brutal flogging of a convict and the note at the bottom reads :

"The flogging of Charles Maher ... 250 lashes ... single flogger.

The description on the next page reads : "Thursday 11th, I well remember the date. Began the most stormy weather on record here the cascade was partly destroyed. The flogging of Charles Maher almost brought about a mutiny. His back was quite bare of skin and flesh. Poor wretch he received 250 lashes and upon receiving 200 Kimberley refused to count meaning thereby that his punishment was enough." Some of the images and descriptions of punishment that I have come across have been too horrific to include in any detail. |

|

The British Government started promoting Van Diemen's Land as a land of opportunity, and encouraging emigration by settlers, from about 1820.Settlers could apply for a grant of land and some financial aid. Incidentally, the offer was also extended to women, in an effort to even up the numbers of men and women on the island. Men outnumbered women by an enormous number. |

|

The promotional literature reads like a gazeteer with fanciful and attractive descriptions of what life would offer! However, a report from 1843 criticises this policy as it didn't prepare the would-be-settlers for the dangers, problems and harsh realities of what would be a difficult, pioneering existence. |

|

The Van Diemen's Land Company was formed in 1824 by a group of London merchants who planned to farm sheep and export the wool to Britain, for sale in the rapidly expanding spinning and weaving industries, back home. The company was allocated 250,000 acres in the north and the north west. Although already a large land grant, it was only half the number of acres actually requested but still dispossessing the aboriginal tribes already there of considerable areas of tribal hunting grounds. The Company's headquarters would be at Circular Head, in the extreme north-west. For a number of years it struggled to become the successful and profitable enterprise envisaged but it eventually prospered and still survives today. One source of their problems came as a result of their intolerant attitude towards the aboriginal people and the violent attacks by their workforce upon them. Antagonism on both sides escalated and came to a head in 1828, in what became known as the Cape Grim massacre. In this terrible incident, a group of tribespeople, collecting food by the shore, were the victims of an unprovoked attack by Van Diemen's Land employees. About 30 tribesmen were chased down and deliberately murdered. |

|

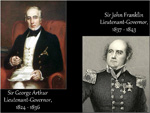

At the time of Edwin's arrival, Sir George Arthur was Lieutenant Governor of Van Diemen's Land and in office from 1824 to 1836.

He was followed by Sir John Franklin, who was Lieutenant Governor from 1837 - 1843 |

|

Escaped convicts and criminals fled into the forests and mountains and, lacking hunting skills, found little to eat. They became known and feared as 'Bushrangers'. A newspaper item, from the week Edwin arrived in Hobart, is a report of a cave being discovered and evidence of bushrangers living in it. Although their more notorious activies were in the years before Edwin's time, they were still very much in evidence, as the dozens of newspaper reports show. Another report was from the 26th November, just 2 weeks later, and concerned a policeman being ambushed and shot whilst escorting a prisoner back to town. |

|

When the Convicts landed they were assigned to whatever occupation would benefit most from their expertise. The convicts could be assigned to work-gangs, wherever a road, a bridge or a building needed constructing; or wherever forest and jungle needed cutting back; or to individual 'masters' who needed a small, cheap workforce. Farmers and agricultual workers would probably be sent to work on farms, where they would live and work. Men who had been educated and were literate, might be sent to work in local offices etc., or to small business men, again to live and work in that place. The 'masters', in these instances, would be responsible for feeding and clothing the workers. Generally, blacksmiths, carpenters, masons, coopers, wheelwrights and other such artisans were valued servants and, as such, when assigned to a master, could hope for better conditions in return for working well. |

|

On arrival, convicts were given a set of clothes which identified them as convicts, when they were out and about. In a small number of instances transportation could open up opportunites, for the literate or hard-working, reliable convicts, that could lead to their successful integration into the community, when they were released. |

|

Edwin landed in Hobart a few days short of a year since he was sentenced, in far distant Salford. It must surely have seemed a lifetime ago, even, a forgotten world. As you first come across the following terms, some of them may seem to overlap in meaning, as it were, but, as you can see, they are completely different. These definitions are taken from the National Library of Australia website. A TICKET OF LEAVE allowed convicts to work for themselves provided that they remained in a specified area, reported regularly to local authorities, attended divine worship every Sunday, if possible. They could not leave the colony. A CERTIFICATE OF FREEDOM was issued at the completion of a convict's sentence as proof that he/she was a free person. They were free to travel anywhere and could return to Britain (if they could afford it!). A CONDITIONAL PARDON allowed convicts with life sentences freedom of the colony but they were not allowed to return to Britain. An ABSOLUTE PARDON gave a 'lifer' complete remittance of sentence. The convict had freedom of the colony and could return to Britain. |

|

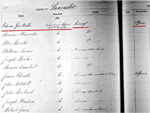

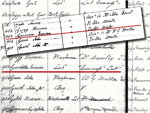

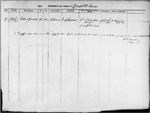

When Edwin arrived, his details would be entered into a 'Conduct' Register which would follow him, throughout his years of penal servitude. As a convict, the men would not be dignified by use of their names, they would be known just by their number, in Edwin's case, 953, which would probably have been given to him, back in England, when he boarded the 'Isabella'. The pages, in the Register, seem to have been ready-ruled to hold 3 names and we can see from the bits of entries visible on the next page, that there were three convicts who, with Edwin, appear to have shared similar experiences as the sections are filled completely and we can make out words such as, 'absconding', 'Port Arthur', 'hard labour', 'suspicion of felony', 'solitary confinement on bread & water', and so on. The writing on the Conduct Register is not easy to read, and many words are abbreviated, however, trying to piece together the entries near Edwin's, for comparison, we can read that number 952, was a 'Richard Griggs' who had been sentenced at Hythe, in Kent, on the 29th December 1832, the same month and year as Edwin. They were both transported, for 7 years, on the same ship, at the same time. A quick search on the internet for Richard revealed nothing more than the notice of his being sent to start his sentence on the Hulks, in February, namely on the 'Cumberland', as was Edwin. I could find no date of birth that might have been his and no indication of his age. On the entry for Richard Griggs we can make out that : He was transported for the theft of 2 bushels of beans. The Gaol Report showed 'Temper good' but former something (words illegible), was 'bad'. The Hulk Report was 'Orderly', and he was single. He acknowledged that his offence was the theft of 2 bushels of beans. He had been transported before, about 15 years previously for theft of hay, and sent for 7 years. He had served 3 years 8 months at Sheerness, once, for poaching. Truly heinous crimes! He was also recorded as '3 months widower 3 children' ... who would care what became of them? Earlier on the page he says ' he is single'; was this how he considered his widowed situation? The surgeon-superintendant's report was 'orderly. His record goes on to show that he received a ticket of leave on the 14th November 1838 and a Certificate of Freedom on February 22nd 1839, 6 years after he was sent to the Hulks. Apparently, in his time in Van Diemen's Land, he had not looked for trouble and was not recorded as having been guilty of any further misdemeanours. |

|

Edwin's is a far sorrier tale than the other two entries on this page. We can make out that he was transported for the theft of 5 waistcoats. His gaol Report is that his 'Character is indifferent'. His Hulk report reads 'orderly'. He was single. He acknowledged his offence was the theft of 5 waistcoats. The surgeon-superintendant's Report was, 'orderly'. There is a note at the side which reads: '7th April, 1837, original sentence extended by 3 years'. Brutal ... what could he have done to deserve that? I've transcribed what I could of what's on the page but I've not used the abbreviations. I thought that the Capital letters between the forward slash signs were the initials of the complainant and, where I thought I could second-guess an illegible word, I did: December. 9th 1833 absent without leave. June 24 1834 Strong suspicion of taking the thighs of two cows, the property of his master, 3 years Imprisonment and hard labour and strongly recommend for Port Arthur. |

|

December. 10th 1834 Chain Gang / Refusing to go to his work, 50 lashes. March 9th 1835 In reply / Profane swearing, 6 weeks Imprisonment and hard labour on Long-Meadow Chain Gang August. 25th 1835 Bullock Drivers / Neglect of work, 20 lashes. April 20th 1836 / Insolence, 10 days hard labour on the Road Gang. / then to undergo [something I can't read or guess] at Riley's Ford Road Gang; then to be sent afterwards to Morven. Vide Lieutenant-Governors Decision.12th May 1836 (Vide meaning 'see' ) Sept. 27 1837 Embezzlement - Committed for trial,12 months probation, Campbell town, to be reported. Vide Lieutenant-Governors Decision. 21 Oct. January 3 1839 Drunk, Cells and Bread & Water for 24 hours. 30th Oct.1839 / Charged with stealing wheat under the value of £5, to be kept to hard labour in chains for 12 calendar months and to be sent to Port Arthur. Port Arthur Chain Gang conduct to be referred. Vide Lieutenant-Governors Decision./Nov.1839. May 25th 1841 / Disobedience of orders and of duty, 6 Months Hard Labour, 3 Months of which in Chains on Jericho Chain Gang, then Cleveland out of Chains. Vide Lieutenant-Governors Decision.. 28/5/41. This sentence would take him up to the end of November 1841 |

|

The final entry on the register page shows that Edwin received his Free Certificate, No. 868, in 1843, after 10 years of brutalising and humiliating servitude. |

|

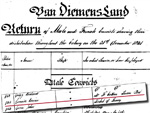

So, where was he in 1842, a year before he was freed? This is the opening page of the Convict Return for 31st December 1841, in which all the convicts, throughout the colony, were listed. In this return, Edwin is recorded as being assigned to Mr. F. Cotton, of Swan Port. As far as can be judged, this is where Edwin probably remained until he received his Certificate of Freedom, a year later. |

|

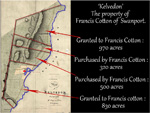

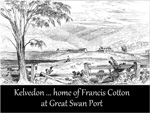

Quite a lot is known, and written, about Francis Cotton, a Quaker. Referencing the Australian Dictionary of Biography, we can read that, he was born, in 1801 in London,and educated there. He served his apprenticeship as a builder and set up his own business before emigrating to Van Diemen's Land, with his wife, in 1828. Having ambitions to become a landowner, he explored the central areas of the island but found nothing to tempt him, that wasn't already settled. |

|

He then turned his attention to the east coast and, undeterred, after several serious setbacks, he prospered in sheep farming, around Oyster Bay. Amongst his entrepreneurial enterprises he exported high quality fleeces, and wattle bark to England and sent wheat to Hobart. He extended his initial land grants with 2 further land grants and also, as we can see from this example, 2 lots of land which he purchased. I also came across his name in 'A Narrative of a visit to the Australian Colonies' by James Backhouse, written in 1843. It was in connection with George Augustus Robinson, the man who masterminded the final re-settlement of the aboriginals on the islands. Cotton acted as Robinson's guide, as he looked for suitable re-settlement areas. It was this forceful businessman with whom Edwin would probably serve-out his final year of servitude. |

|

By the time Edwin was assigned to Cotton, his new master was already successful and had built his family home and estate which he called 'Kelvedon'. Unfortunately, because of Cotton's many and varied business interests, it's not possible to know in what capacity Edwin would be working but, I think it's safe to assume that it would be labouring in some way. |

|

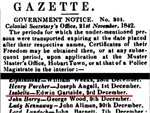

This is the GOVERNMENT NOTICE. No. 304, printed in the GAZETTE, which reads :

And there he was! The 'Isabella' - Edwin Gartside, 3rd December. |

|

It would have been lovely to end the story with a paragraph about Edwin's life in later years ... that he became a succesful craftsman or farmer; married and had children; any outcome, as long as he seemed happy. It would have been just as good, to write that he returned home to the family. But it wasn't to be. Edwin died in July 1844, age 30, having been a free man again for barely 18 months. Where he spent those months, or what he did, I have no way of knowing. Cause of death is recorded in the register as 'emphysema' which is, according to the NHS website, 'damage to the air sacs in the lungs causing breathlessness and difficulty breathing'. His death is registered in Campbell Town. Had he gone there looking for work? Was he in hospital? We can't know ... |

|

Although letters between convicts and those left at home seem to have been possible, somehow, it seems hard to believe that Edwin would have been in contact with family at home, even if we can believe he might have been literate. After all, what could he have written about? He had no obvious plans to keep his 'head down' and earn remission of his sentence; and would he really have wanted to let his family know of his sufferings and brutal treatment? It's also unlikely that the family would have actually been anticipating his return as so few convicts actually returned home. On a last, sad thought, did the family ever know that he had been given his freedom,or that he had died? In reality, he had been lost to them in December 1832, |

|

Resources with on-line access to material

:

Internet Archive:

Transcription of 'Register of Oldham News and Reports' by Edwin Butterworth Book Publication A Centenary History of Oldham by Hartley Bateson, Pub. 1949 Article: Transportation of English Convicts after 1783 by James Edward Gillespie. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Vol. 13; issue 3, 1923 Websites: Companion to Tasmanian History Subscription websites: |

|

by Sheila Goodyear |

|

Members' Pages MENU

Family History Page MENU